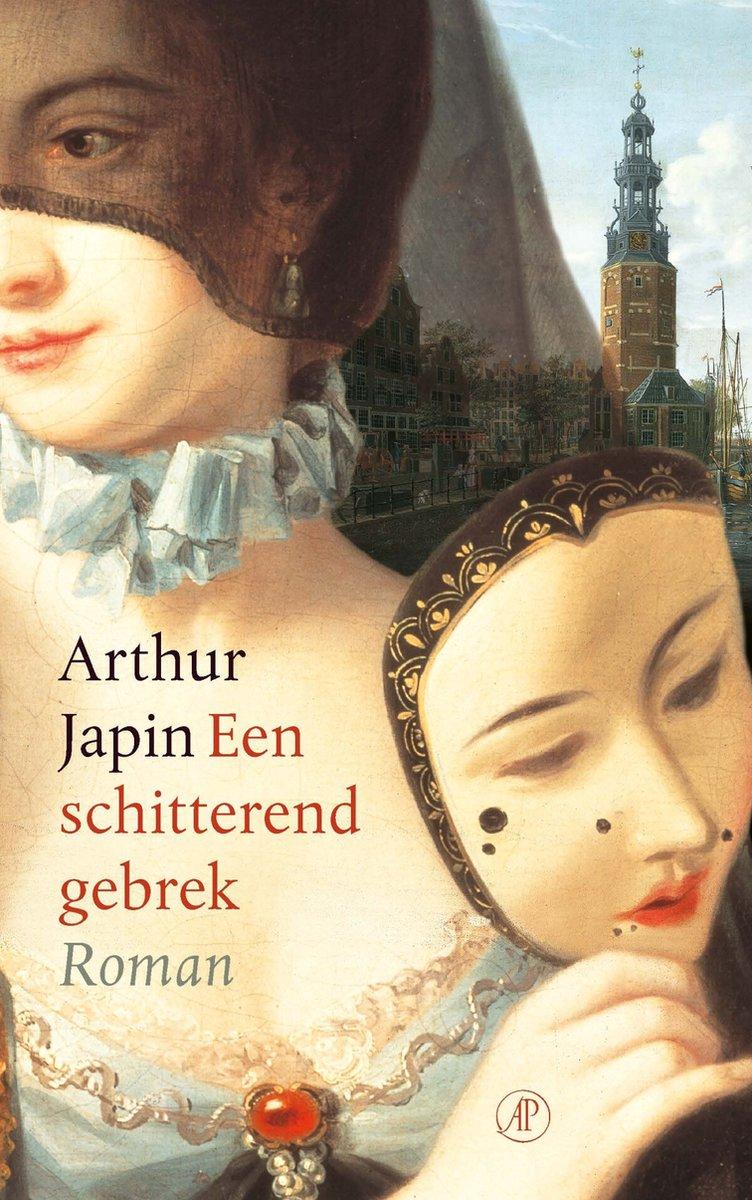

In Lucia’s Eyes

Arthur Japin found his inspiration for In 'Lucia’s Eyes' in an episode in the life of Giacomo Casanova, philanderer and bon vivant. In his memoirs Casanova tells of being invited to the country estate of Pasiano as a sixteen-year-old and falling hopelessly in love with the breathtaking Lucia, two years his junior. She has only one splendid flaw: ‘She is too young.’ Because of Lucia’s genuine innocence he does not bed her, promising instead to return in six months to ask for her hand in marriage.

When Casanova returns to the Italian manor, Lucia has disappeared, supposedly because she has become pregnant by a messenger and has run away with him. Casanova is consumed by regret at not acting when he had the chance. Years later, on a visit to Amsterdam, in 1758, travelling under his nom de plume Chevalier de Seingalt, he sees her again, in a brothel. She has changed so much that he barely recognizes her: ‘Lucia was not so much ugly,’ writes Casanova, ‘as something much worse: repugnant.’ In this historical novel Arthur Japin speculates on what could have happened to Lucia. He proposes in In Lucia’s Eyes that she hadn’t got pregnant, but had suffered a worse fate in a world where a woman was judged solely on the basis of her appearance: she caught smallpox which left her face so disfigured that she was afraid to look Casanova in the eye again. Lucia had been unwilling to provoke his pity or compromise his reputation and position by holding him to his promise.

She felt she had had no choice but to flee and earn her living as a prostitute, hidden behind a veil that she never removes and an alias Galathea de Pompignac. When Casanova turns up in Amsterdam, his desire for her is reawakened. They try to outdo each other in razor-sharp dialogues which are reminiscent of the verbal sparring matches between Mme. de Maintenon and Comte du Valmont in Laclos’ famous Les liaisons dangereuses; Arthur Japin plays with bourgeois, eighteenth-century conventions to the hilt. The tragic love of Giacomo and Lucia is continually strained by worldly, emotional and philosophical differences, between men and women, outer and inner beauty, reason and intuition, and imagination and reality, all typical of the Enlightenment, as well as of the ambiguity that love still possesses, even now.

With this novel Japin has won the Libris Literature Prize for best novel of the year 2003.

A beautifully constructed story, suffused with the atmosphere of an Enlightenment novel. (…) Simply put, a rich novel.

Vrij Nederland

Japin has written an engaging, exciting and moving novel, complete with a solid plot, witty dialogue, surprising twists and an unexpected denouement.

NRC Handelsblad

.jpg&w=640&q=75)