The Sponger, Young Titans and Little Poet

'The Sponger' (De uitvreter) and 'Young Titans' (Titaantjes) take place within a circle of young bohemians in the years leading up to the First World War. 'The Sponger' is the story of Japi, a likeable bon vivant, who tries ‘to wither away, to become indifferent to hunger and sleep, to cold and damp,’ but who can also fully enjoy the good things of the world, especially if somebody else foots the bill.

The painter Bavink introduces him to his Amsterdam friends, where Japi, because of his idiosyncrasies, soon becomes known as a ‘sponger,’ a sobriquet that he manages to twist into a title of honour. He’s unable to sustain such a free life, however, and the story ends in his suicide.

Young Titans (Titaantjes) is about the same circle of friends – minus Japi but with a few new figures: five boys fired by a vague idealism. In scene after scene we watch as the ‘nice guys’ waste away. All are forced to abandon their ideals, and only Bavink is ‘defeated by those “God damned things?’ and finally goes insane.

The story Little Poet (Dichtertje) is about the same problem, but this time within the context of marriage. The poet is happily married, but ‘if you’re a poet, the prettiest girls always walk on the other side of the canal,’ and he comes under the spell of his sister-in-law. This story, too, has an unhappy ending. It is the most literary story of the three because God and the Devil become involved in the poet’s life, as they do in Goethe’s Faust.

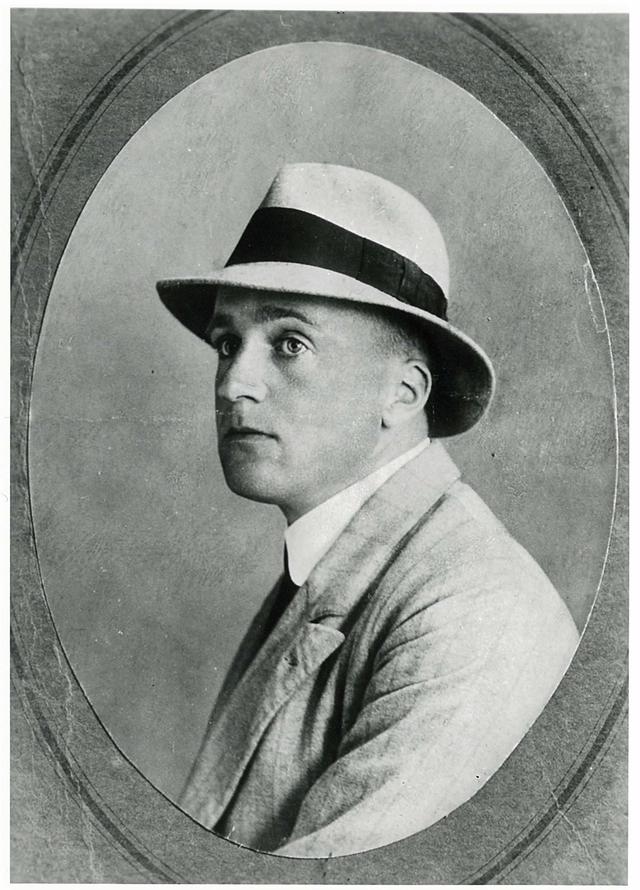

The ‘plot’ of the stories is really incidental in a certain sense. All three provide a splendid picture of Amsterdam at the beginning of the 20th century and testify to a great love of the Dutch landscape. But the most extraordinary thing about them is Nescio’s style of writing. His utter simplicity goes hand-in-hand with a great command of humour, irony, matter-of-factness, understatement and sentiment (never sentimentality or self-pity), all of which miraculously balance each other out.

Nescio’s subject matter is best expressed in opposites: freedom versus confinement, a longing for eternity versus the notion of mortality. The stories demonstrate that the individual is no match for the world and helplessly comes to grief if he tries to resist or becomes engrossed in the big existential questions. For, as the final sentence in Little Titans puts it, ‘woe be unto him who questions why.’

Nescio is essentially a lyricist, a poet writing in prose. But he’s a cynic, too, as well as a mystic in his own way. Like Chekhov or Turgenev, he is able to express complicated matters in simple language. And the fact that his work is still so light and playful, so tender, moving and outrageously funny is nothing short of miraculous.