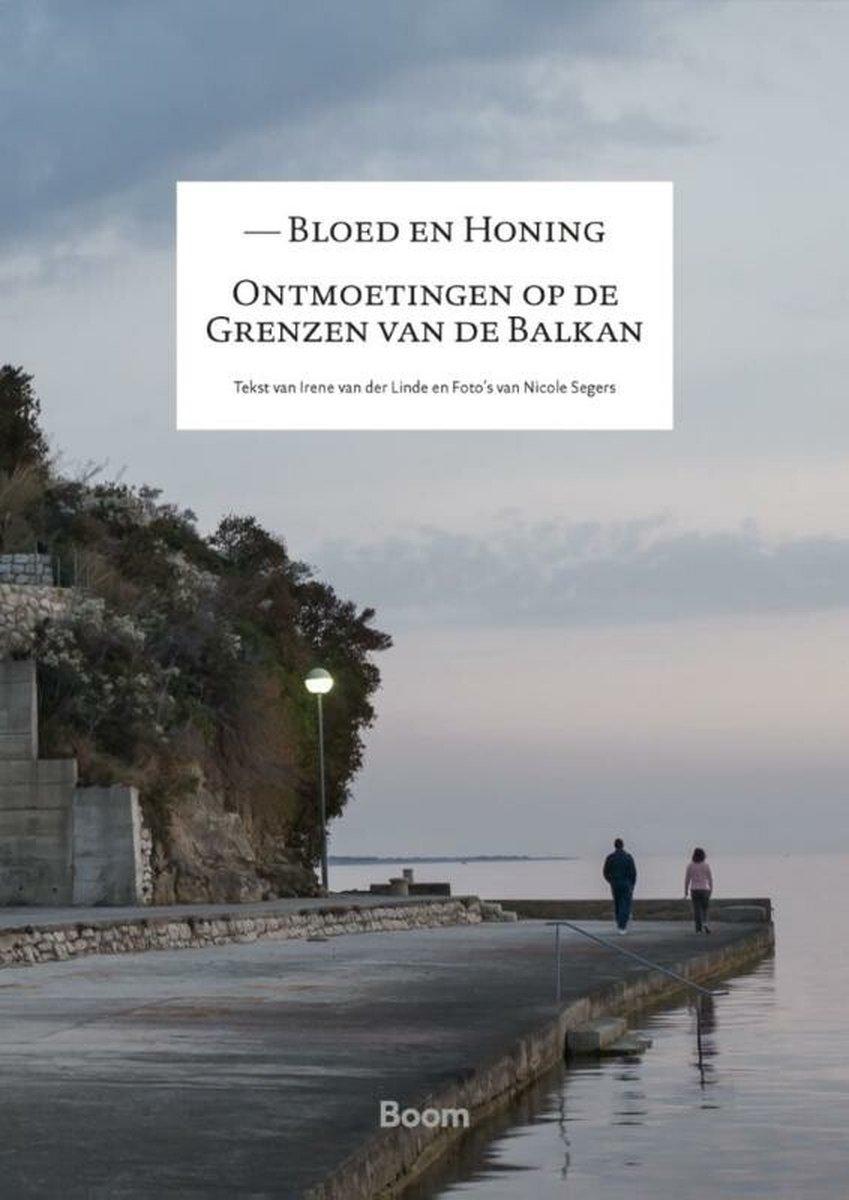

Blood and Honey

In 1937, the British writer and journalist Rebecca West travelled through the Balkans. Everywhere she looked she found traces of the meaning of its name, derived from the Turkish: ‘bal’ – honey, ‘kan’ – blood. More than eighty years, and many wars and attempts at reconciliation later, Dutch writer Irene van der Linde and photographer Nicole Segers set off in her footsteps, visiting the seven countries that now form the Balkans. They search for the meanings of the new borders in Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Kosovo, Albania and Montenegro.

They travel along deserted roads and over barren plains, through dark rocky gorges and abandoned villages. They visit Dubrovnik, Sarajevo, Skopje, Ohrid and Tirana and meet artists, scientists, dreamers, fighters and the forgotten. The reader is taken to remote corners where at first sight time has stood still. On this journey they are also confronted with horror, such as the bridge in Visegrad upon which thousands of Bosnians were murdered and then thrown into the river in 1992, and with the nostalgia of cosmopolitan, opulent Sarajevo, where a woman in their hotel prepares a dish from the Habsburg era. Hope for a better future is hard to find, even though much has changed since the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s.

Van der Linde and Segers argue that it is precisely in the Balkans that we need to think about the future of Europe. What Rebecca West saw – different peoples, who nevertheless lived peacefully side by side – is exactly what the authors of Blood and Honey don’t see: nowadays the predominant mood is embitterment and nostalgia for a unitary state. The fragmentation and division is unprecedented, ultra-nationalist politicians meet with extraordinary success, nobody seems to have dealt with the trauma of the Balkan wars. Ensuring democracy on the fringes of Europe is all the more urgent. ‘Don’t think it won’t happen, that there won’t be a war. The world you live in, which you consider normal, can disappear in a puff of smoke. Nobody believed it, we didn’t either, but it happened anyway,’ historian Jesenko Galijašević warns in Sarajevo.

Blood and Honey tells of unity and separation, of the sobering reality of nationalism put into practice. It tells of hope and disappointment, passion and lethargy, day-to-day worries and geopolitical forces, and of fragmentation, as is happening elsewhere in Europe. Language and image are intertwined in this unique example of slow journalism, a mix of literary non-fiction and documentary photography.

Everyone should read this book about a forgotten corner of Europe.

NRC Handelsblad

Heartbreaking and truly beautiful.

Lieve Joris, renowned travel writer