Criminal Case 40/61

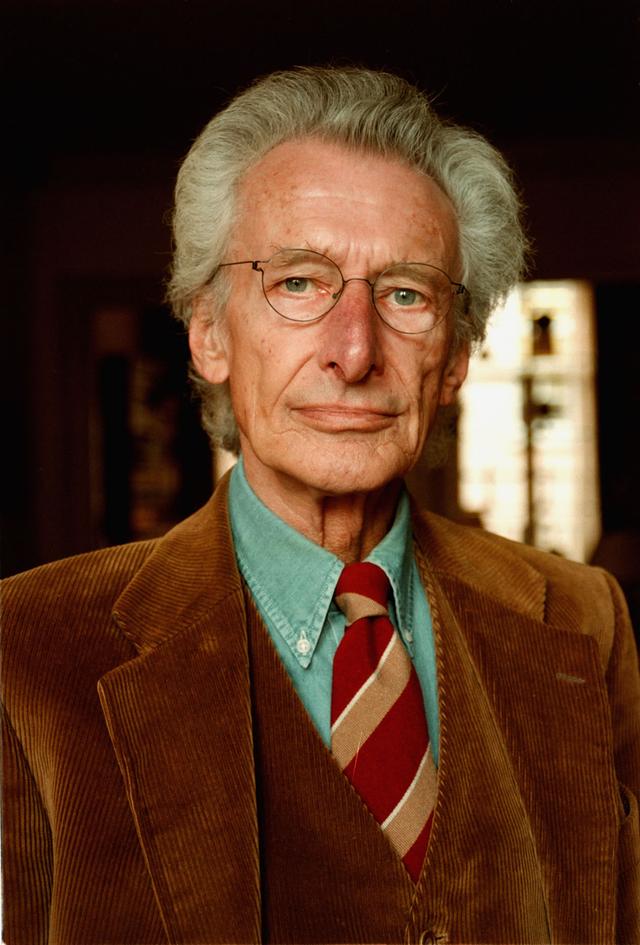

In her preface to 'Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil' (1963), Hannah Arendt tells us that the Dutch writer Harry Mulisch is one of the few to have shared her views of the character of Adolf Eichmann, the organiser of the Holocaust. In 1961, Mulisch went to Jerusalem to report on the Eichmann trial for a Dutch weekly. His articles were collected a year later and published as 'De zaak 40/61'.

Mulisch modestly calls his book a report, but it is much more than that: a personal and most disturbing essay on the Nazi mass murder of European Jewry as brought out in the Eichmann trial. Mulisch’s stake is high. He does not confine himself to the case alone, but takes a leap into speculating on the destructive drive in contemporary art, which found its unintended culmination in ‘Auschwitz’. Not that Mulisch blames the artists; he believes there is a deep and fundamental gulf between art and reality.

The artist’s destructive imagination was more a form of resistance to the ‘new element whose approach they viewed with alarm’. That new element was embodied in Eichmann, whom Mulisch considers ‘the symbol of Progress’. Unlike the ‘mythical hero Hitler’ and his faithful disciple Himmler, Eichmann may not even have been a convinced anti-Semite. He simply carried out orders, regardless of the moral consequences; he was an anonymous technocrat, ‘not so much a criminal as a man who stopped at nothing.’

Mulisch typifies him as ‘the smallest of men’, behind whom modern technology loomed; this is an idea that also plays a crucial role in Mulisch’s novels. The dangers of modern technology, which at their most banal were made manifest in the person of Eichmann, force us to examine and reflect upon ourselves. For Mulisch, Eichmann is not some inhuman devil, but the person we all see in our mirrors. The question of morality that this raises is what Mulisch tries to answer with imagination and sensitivity in De zaak 40/61. The essay has lost none of its topicality.