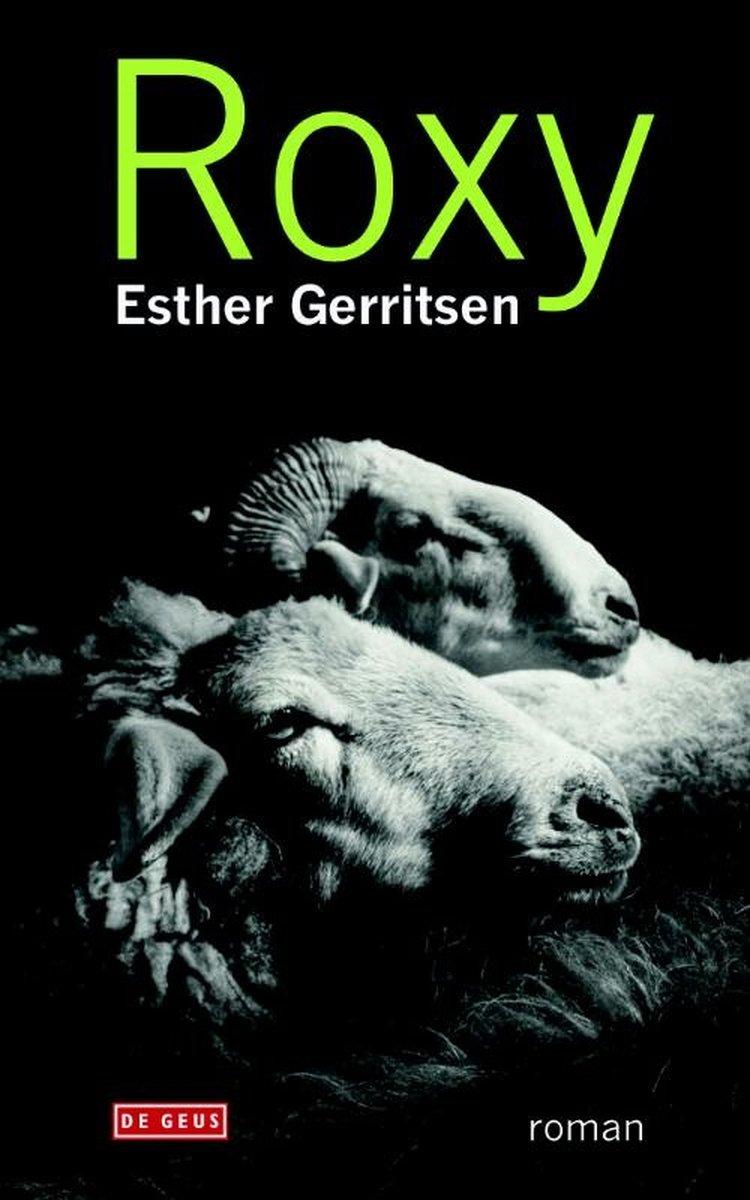

Roxy

Esther Gerritsen has written a novel about a confused woman who does something gruesome, but her style allows readers to sympathise with this tragicomic anti-hero. Few writers are as good at dialogue and absurd situations as Gerritsen, who delves into themes such as mourning, growing up and parenthood.

In the middle of the night two policemen appear at the door of 27-year-old Roxy to inform her that her husband, a successful TV producer, has been killed. He has had an accident together with his mistress; both were found in the car naked. Roxy, who at the age of seventeen fled from the home of her oafish father and alcoholic mother into the arms of her husband, knows that life has now become serious: ‘She always knew that she’d skipped something, that she’d taken a shortcut to adulthood.’

Bringing up her daughter Louise is no longer a game. She suddenly has to deal with people who come into the house: Jane, her husband’s assistant, and Feike, her daughter’s babysitter. Worse still, she has to operate the terribly complicated espresso machine. Roxy is perceptive, but doesn’t know how to cope, not even with her parents, of whom she is permanently ashamed. Sex with the undertaker only brings temporary relief, so she decides to go on holiday with her daughter, the babysitter and the assistant. What follows is a road novel in which Roxy tries to make friends with Feike and Jane but just as easily swaps their company for anonymous sex with young men.

The holiday makes it clear that Roxy finds it difficult – if not impossible – to relate to other people. One night the isolation and frustration become too much. She wants to avenge herself, not on human beings, who are ‘dead, drunk, absent or innocent’. So she seeks a suitable enemy and finds it in a herd of sheep.

Once again Esther Gerritsen displays her gift for striking sentences and dialogue that teeters on the thin line between normality and alienation, between entertaining kookiness and harrowing absurdism.

De Volkskrant

There are sentences carved in stone: ‘Roxy is looking for new words, but her youth has already become a book that she is retelling.’ With that, Gerritsen succeeds in catching the haunting and dark precision of someone like Samuel Beckett. If this won’t lead to a shortlist nomination for one of the biggest prizes, I’ll eat my hat.

De Morgen