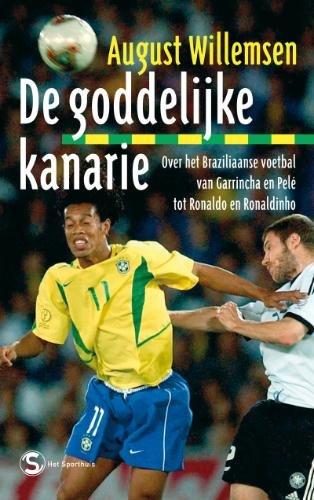

The Divine Canary

The Netherlands has been a world-class footballing nation since the early 1970s, but only in the past twenty years has a tradition of football literature sprung up. Oddly, the best of them, 'The Divine Canary', is not a book about Dutch soccer but a compelling socio-cultural sketch of Brazil in the light of its love of football.

A translator from Portuguese, August Willemsen is in a good position to draw on the work of great Brazilian writers for whom football has been an acceptable literary subject for many years. He quotes a poem about football by Carlos Drummond de Andrade, Brazil’s most important twentieth-century poet, which includes the lines: ‘My eleven athletes / are eleven children, lashed / by a futile god who rules their fate.’ Then there is Armando Nogueira, a writer who sums up the fascination for the game in the maxim ‘God is round’ and claims that ‘To understand a Brazilian’s soul you much catch him at the moment of a goal.’

Willemsen does exactly that, with colourful observations, analyses and anecdotes. He uses many goals and considerable understanding to lay bare the soul of Brazilian football and with it the soul of the land where he spent many years of his life. He colours in the blank early days of Brazilian football with an anecdote about Carlos Alberto, a mulatto who played for the great club Fluminense and whitened his face before every match with pó-de-arroz, or ‘poudre de riz’, a kind of perfumed talc that fashionable ladies had been using on their faces for generations. Even today, decades after the marvellous feats of black footballers like Pelé and Garrincha, fanatical fans of clubs playing against Fluminense accuse them, in thunderous unison, of being ‘Pó-de arroz!’, which demonstrates for Willemsen the historical awareness of Brazilian football fans.

The Divine Canary is also the story of the author’s own love of Brazilian football. According to Willemsen, the ‘canaries’, as the yellow-clad Brazilian internationals are known, displayed their ‘divinity’ in the years between 1956 and 1970, with players like Garrincha, Pelé, Jairzinho and Rivelino. Willemsen is content to make an exception of 1982, but he is not impressed by the football played by the Brazilian World Cup winners and finalists over the past twenty years; it is simply not ‘Brazilian’ enough.

It is precisely through this repudiation of the recent performance of the canaries that Willemsen points to the essence of an ideal: the canaries are first of all ‘divine’, a concept they need to live up to.

It is literature, an ode to Brazilian football and, above all, to the talents of individual Brazilian players.

NRC Handelsblad

For a few hours a Brazilian amongst Brazilians. That’s the liberating sense of joy that awaits the reader of The Divine Canary.

Trouw