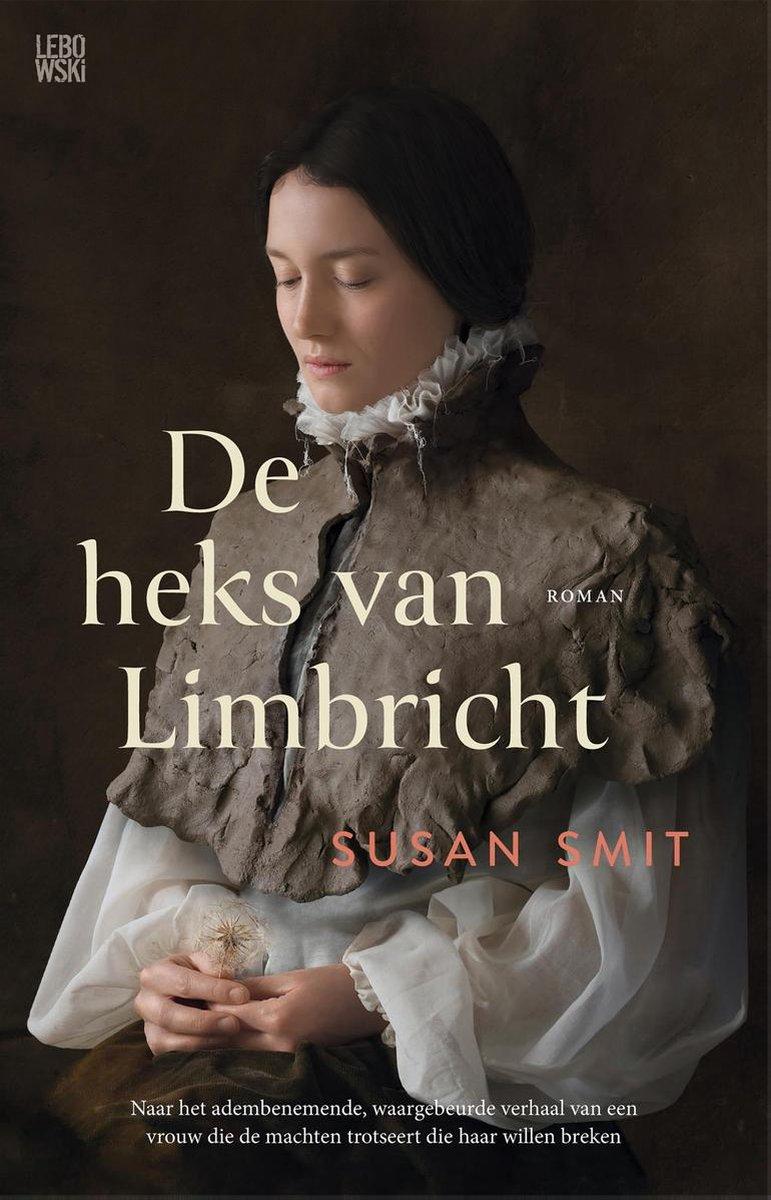

The Last Witch Hunt

Women who are unafraid to stand up for themselves and others often get the epithet ‘witch’ hurled at them. In online discourse, you see it all the time in reference to strong women like Nancy Pelosi, Kamala Harris or Sigrid Kaag and Khadija Arib here in the Netherlands. In her novel 'The Last Witch Hunt', based on historical research, Susan Smit shows how this kind of nasty talk can have serious consequences. In July 1674, soldiers raid the home of 74-year-old Entgen Luijten. She is taken to the castle in Limbricht, a town in the southernmost part of the Netherlands, and locked in a dungeon where she is told that, based on a number of incidents, she is being accused of witchcraft or black magic.

As messenger to the Earl of Limbricht, Entgen’s father has had responsibility for making sure that the cattle farmers use the shared pasture in accordance with the agreements. Entgen often accompanies him as he makes his rounds: she shares his love of nature, and they have an unspoken understanding. Her recalcitrant grandmother, who teaches her all about herbs and plants, is another important influence in her life.

Her relationship with her very pious mother is much less close. There is a large age difference between Entgen and her younger siblings, and she ends up being responsible for their care. Entgen realises at a young age that she is different from other people. When she chooses Jacob Bovendeert as her husband, she is aware of the advantages of that choice and of her own sexual desires. In her marriage, she demands to be at least equal to her husband. She takes the lead in many situations, led by her temperament.

She helps to organise an uprising against the Earl of Limbricht, who is exploiting his tenant farmers. Even in years when the harvest is meagre, the farmers have to give him ten percent of their yield. As a woman she isn’t allowed to join the fight, but she encourages Jacob to go. During a second uprising Jacob disappears. Entgen suspects the earl has made him pay the price for her big mouth. But losing her husband doesn’t break her spirit. She doesn’t find it difficult to be alone and she uses her knowledge of nature to get by. Her harvest tends to be more abundant than that of her neighbours.

Smit portrays Entgen Luijten as an emblem of female indomitability. During the cross-examinations, Entgen doesn’t mention the names of any other women, because she knows all too well what would happen to them. Despite being locked in a cold, dark prison cell and being starved and tortured, she doesn’t yield. In a society where women are considered the ‘weaker sex’ by the church and the authorities, susceptible to Satan’s temptations, Entgen stands out as wholly individual, a wise and autonomous human being.

Smit’s empathy is her great strength. She doesn’t sugarcoat or romanticise; she sweeps the fairytale off the table.

NRC Handelsblad

This novel gives important insight into how the judiciary, the church and the powers-that-be were able to silence outspoken women.

Zin